Luderitz is, as I suspected, is nothing to get too excited about – a pretty little harbour town on a windswept and inhospitable Atlantic coast. I wander around, spying German colonial architecture, seals and penguins and a discontinued railway line (that, once upon a time, went all the way to Keetmanshoop).

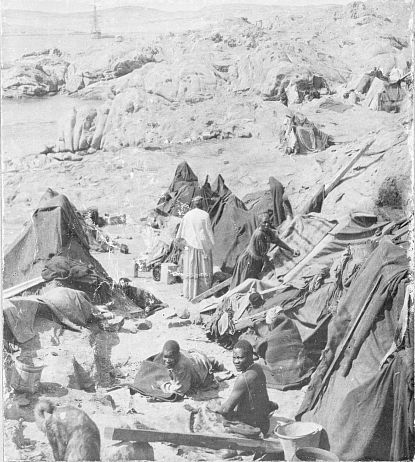

The darker side of the place I don't hear about until a chance encounter with a local over breakfast next day. Apparently, the nearby Shark Island served as a forced labour camp at the turn of the century, with the Germans in charge using thousands of indigenous Herero and Nama people to kick-start heavy and dangerous constructions projects. I ask her how they were transported here and the answer is hard to hear - by cattle car to Swakopmund (way north) then by boat to Luderitz. She tells me rape and malnutrition were widespread, medical research was carried out on the skulls of dead prisoners and that thousands died.

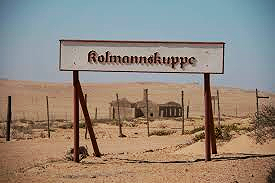

This is the point at which I decide I can hear no more and call for the bill. I'm not one to shy away from politics, but if I listen to any more of her stories I'll throw myself off the harbour in despair. Colonialists all over the world raped, pillaged and murdered people in the name of their Empires and the more I travel the world, the more of these atrocities I'm hearing about. I remind myself of the purpose of this visit – a journey out to a tiny place, about 10 kms away from here, which goes by the name of Kolmanskop. Why has it caught my eye? Because it's a town that went from boom to bust – as a result of a Diamond Rush and a subsequent Diamond Crash. At its heyday just after the turn of the 20th century, by 1956 it had been deserted entirely. Today, it is a veritable Ghost Town, but with a twist. All of the buildings, now laying in ruins, are covered in huge piles of sand that have blown in from the desert! Now this is a sight I have to see.

But the next morning, when I arrive at the tourist office, cash in hand, hoping to purchase the required permit, the woman behind the desk tells me the group has already left. I'll have to return tomorrow, she can't help me, no, and nor can I visit there alone. That, she informs me sternly, is forbidden. Ah, verboten? We'll see about that. I have no intention of sitting around all day and, naturally rebellious, her Teutonic manner has now made me even more determined to make it there. I decide it's worth taking a chance and walk to the main road. As I suspect, I get a hitch quickly and within 10 minutes I'm at the front gate of the site.

But the main entrance is locked! Inside, I spy the group (I can hear the guide giving her introductory spiel...) Damn! Then, out of the corner of my eye I spy a young boy, the other side of the gate. And he spies me. He motions to me to walk round the side of the fence, which I immediately do. And there I see a side gate, hidden away. Ha! We barter a bit, but not for long (he knows I want to get in, I know he wants hard cash). So $5 later, the deed is done and he hushes me in.

I wander far from the group in the next 90 minutes and bump into a Dutch photographer who has a permit but, like me, isn't a fan of group tours. His book tell us that this town once boasted a theatre, hospital, bakery, power station, ballroom and skittle alley (!) It was the first town in the entire region to own an x-ray machine! Rumour even has it that at the height of the diamond frenzy, bar maids there would have their wages paid in the sparkly things. As we wander from house to house, all knee deep in sand, we are in disbelief.

It's utterly empty and eerie. In one home, wading through almost a metre of sand, I feel an air of complete desolation. It's hard to imagine what it was like here originally, when families turned up in droves, thrilled at the prospect of striking it lucky and making a fortune. By the early 1920s, apparently over 1000 people (German colonialists, their children, and local workers) lived here. But as the price of gems fell, little by little, people deserted the town. Boom to bust in less than half a century, it was left to the mercy of the elements – in the shape of harsh, relentless sand that blew in. No surprise then that the buildings crumbled and are now in ruins, shells of their original elegant structures.

It's a surreal wander around the abandoned town, wading through sand, and at times I actually feel a little dazed. It is utterly surreal – abandoned, ghostly, unloved. This, I remind myself, was once the nerve centre of Namibia's diamond rush. And look at it now. Prosperity to decay. This place should be a lesson to us all that nothing stays the same. Some, I suspect, will find it sad, visiting Kolmanskop. But for a girl like me, who revels in contradiction, it's truly a gem of a find.